Dear Fellow Investors:

The media has been bombarding investors with articles explaining how indexes like the S&P 500 have outperformed the majority of active mutual fund managers. Here’s a smattering of articles from the last 6 months.

- “Investors Pour into Vanguard, Eschewing Stock Pickers” – Wall Street Journal

- “Do Active Funds Have a Future?” –Morningstar

- “When Passive Beats Active” – Barron’s

- “It’s Getting Harder And Harder to Deny the Power of Index Funds” – Business Insider

- “The Decline and Fall of Fund Managers” – Wall Street Journal

- “Can Anything Save Active Management” – CNBC

- “Hello Passive, goodbye active: fund investors make the switch” – Financial Time

An excerpt from Jason Zweig’s August 22, 2014 Wall Street Journal article “The Decline and Fall of Fund Managers” asserts the following:

Active fund management is outmoded, and a lot of stock pickers are going to have to find something else to do for a living.

The debate about whether you should hire an “active” fund manager who tries to beat the market by buying the best stocks and avoiding the worst—or a “passive” index fund that simply matches the market by holding all the stocks—is over.

Financial advisors and registered investment advisors feel severe pressure to throw in the towel on manager selection methodologies and accept index returns. Yet, many of these stories forget one central concept: indexes are actually inexpensive actively-managed portfolios. Every actively managed fund is an index itself.

The recent negativity towards active management invites us to remind readers what we find useful in indexed common stock investing versus the value we find in active management. Under the logic pervaded by the crowd and the media, many managers and organizations are practicing poor performing versions of active management and investors are told, or being shamed into giving up on all efforts to actively manage a common stock portfolio.

First, the primary advantage of the index is that it can be owned very inexpensively. As we have pointed out in a recent webcast and quarterly letter, Warren Buffett cites excitement and expenses as enemies of the investor. The average U.S. equity fund has an annual expense of around 1.37% and the index can be accessed for around 0.2%. The 120 basis point spread dooms many mutual funds to underperformance. Ironically, Warren Buffett is being used as a supporter of indexing because of his belief that most people can’t practice a successful long-duration stock-picking discipline or find a good one to use.

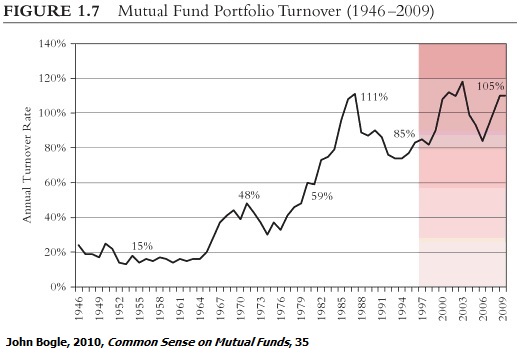

Second, the changes made to the index are infrequent. Over 15 years the S&P 500 Index had a turnover ratio of around 5%. This is tremendously advantageous in two ways. Low turnover means almost no trading cost and almost no premature exit from the best performing securities. The Boston College Center for Retirement Studies showed that the average U.S. equity fund spends 1.44% on trading costs. The Financial Analysts Journal in February of 2013 showed that large-cap U.S. equity funds spend about 0.81% on trading costs.

The added expense is an automatic enemy, but activity is an insidious stealer of future returns by cutting off ownership of what prove to be the best performing securities. Jack LaPorte ran the T. Rowe Price New Horizons fund for 15 years. When he retired he was asked why he had outperformed his peers. His answer was, “…the thing that distinguishes a great growth investor is having the steel will not to trade out of those winning investments too soon.” The performance of all publicly-traded stocks fall on a bell curve and we believe that activity naturally and prematurely cuts off winning long-duration ownership!

In Mr. Zweig’s thesis, he leaned on Charles Ellis, who argues that access to information (via the Internet) and a rising number of well-educated people attempting to pick stocks, renders active management futile. We argue that as information has improved, so has the activity among stock-picking managers. In other words, those active managers have become too active.

Lastly, there is a template for stock selection for the handlers of the S&P 500 Index. They attempt to own the 500 largest U.S. publicly-traded companies which are available for purchase. Turnover is caused by takeovers, business failure and poor stock performance.

Thus far, you’d think we are a fan of indexing. We are, in the same way Warren Buffett is: if you don’t have the ability to practice high margin of safety, long-duration common stock picking and/or don’t have access to someone who does, you are much better off in the index.

There is a lot to like about competing with the index.

Numerous academic studies including Fama-French, Bauman-Conover-Miller and David Dreman, show that valuation matters dearly in their results. These studies show that common stocks which sell at discounts to their similar peers based on price-to-book value and price-to-earnings produce significant forward additional returns (alpha).

Traditional indexes don’t weigh their holdings by valuation and many times gets stuck with massively over-priced securities. At the height of the tech bubble, tech and telecom made up as much as 45% of the S&P 500 Index. There was no discipline in place to reduce ownership of maniacally priced common stocks.

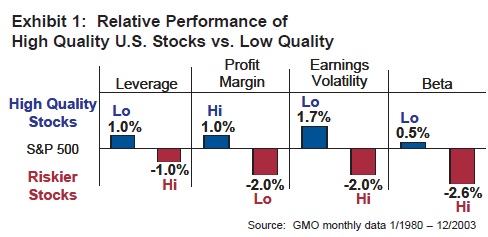

In his seminal study on factors producing alpha, Ben Inker concluded that four factors add to returns over long stretches. They are shown in the chart below:

We believe that low leverage (strong balance sheet), high and sustainable profitability, and low earnings volatility are employable in a discipline designed to outperform the index. We can’t assume backward-looking beta statistics predict the future beta statistics. Clearly, the index has no ability to over-weight any of these factors or even maintain them at the status quo.

In effect, these four factors (cheapness, strong balance sheet, long history of high profitability and business stability) provide an outstanding template for seeking to outperform the index. If they are used in conjunction with the practice of very low turnover, the long-duration common stock owner might be at a big advantage to the index! The only disadvantage would be the difference in annual operating expense and minor trading costs.

Don Phillips, one of the leaders of Morningstar, said this at the recent conference in Chicago: “Mutual fund managers put their results out there for the entire world to see along with a listing of their existing portfolio. But the best thing they do is to communicate to the world about what they are doing.” Nobody from a passive index can write a letter like this about the factors that matter in performance or shepherd investors through a long-duration process like a disciplined active manager.

Warren Buffett, in his seminal guest written article in the Columbia Business School magazine, Hermes, wrote in 1984, “The Super-Investors of Graham and Doddsville.” He explained that everyone he knew who had practiced a high margin-of-safety and long duration common stock discipline had outperformed over a fifteen-year period.

We believe that the changes to our industry will be similar to the changes that have occurred in the past. The money will gravitate to where it is being treated the best. For active managers this means using a stock picking discipline which highlights factors which demonstrate alpha, have reasonable/low annual expenses and practice low turnover. At Smead Capital Management, we love the challenge. Active managers are giving up too much in expense and activity penalties. We like our index!

Warm Regards,

William Smead

The information contained in this missive represents SCM’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve month period is available upon request.

This Missive and others are available at smeadcap.com