There are a great number of bright mathematicians out there who can explain almost everything in common stock selection and portfolio management. One well-known student of the arena is Michael Mauboussin, a Managing Director at Credit Suisse, who recently published a challenging piece of research seeking to explain how difficult it was last year (2014) for mutual funds to beat the S&P 500 Index. In reviewing his analysis, we are reminded that calling stock picking and portfolio management “active management” has done the investment marketplace a huge disservice.

Mr. Mauboussin is not alone. Other well-known industry experts and pundits have weighed in on the current woes of active management as practiced by U.S. equity fund managers. Jeff Sommer of the New York Times, recently wrote about research from S&P Dow Jones Indices. Their work shows that very few equity managers beat the index consistently over a four to five-year stretch.

In contrast to Mauboussin and Sommer, Warren Buffett weighed in on the matter at great length in his Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter and 50-year Anniversary letter on this subject. Mr. Buffett’s conclusion (and ours) is that those who are examining managers use the wrong definition of risk and that active managers are way too active.

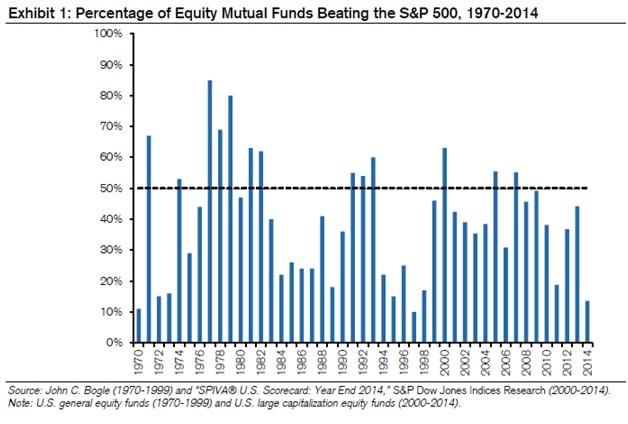

Let’s start with a frequently used chart showing the underperformance of mutual funds compared to the S&P 500 Index:

With the chart in mind, Mr. Mauboussin writes the following:

In the quest for market-beating returns, investors seek money managers who are skillful. But what if skill isn’t the only key to success? … The point of this report is that all of the skill in the world is for naught if you don’t have attractive opportunities.

Mauboussin identifies three ways that a person might be more skillful than other investors: market timing, security selection, and portfolio construction. We at Smead Capital Management would challenge the idea that market timing is open to skill. There have been piles of academic and industry research that refute any claim of merit for market timers, and my anecdotal observations from 35 years in the investment business would only add to that conviction. Cull the list of billionaires in Forbes latest edition and you’ll be hard pressed to find a market timer. Therefore, why include it in the analysis?

Mauboussin goes on:

Certainly, absolute skill in the investment industry continues to rise while relative skill continues to decline. In other words, it’s harder to find markets or securities that are mispriced.

At this point, we wonder why he focuses on this information. First, every statistic shows that professional and amateur investors have dramatically increased their portfolio turnover in the last 40 years. In the U.S. large-cap world the average portfolio turnover is 69% (our six-year average is 13%). This means the average large-cap manager gets a brand new portfolio almost every 1.5 years! A study in the February 2013 Financial Analysts Journal showed that the turnover costs large-cap U.S. Equity funds 0.81% or 81 basis points per year. For this reason, the skill might be high, but it gets burned up in trading costs. It’s like being a great husband and then dumping your wife for a new one every two years—not a good plan.

There is a very important second reason that being way too active may make stock pickers perform poorly in relation to stock indexes. All stock price performance falls onto a bell curve, like any other set of facts in life. All stocks which go to zero had to fall 30%, then 50% and more to go to zero. On the other hand, the best performing stocks over a twenty-year period can rise by ten times their original investment or more.

We as a firm believe that ownership of a great company can be the gift that keeps on giving. Today’s high activity level begs portfolio managers to sell winners too soon and debilitates their long-term alpha in the process. We are sure that the index gains a great advantage from almost never getting in the way of their best performing stocks. The index never over-thinks its portfolio; whereas today’s active management community is prone to do this by way of high turnover.

Since very few stock selectors take a long-duration view, it is highly unlikely that absolute skill or relative skill has gone up in long-term security analysis and stock picking. The statistics on increasing turnover appear to us to be screaming that we are right. We find no coincidence that the world’s most successful investor, Warren Buffett, says that he and Charlie Munger’s favorite holding period is “forever.”

We believe that portfolio construction doesn’t matter in long durations as much as it does in short durations. To get a handle on this part of the discussion we will turn to a recent New York Times article by Jeff Sommer titled, “How Many Mutual Funds Routinely Rout the Market? Zero.” Sommer examines data from S & P Dow Jones Indices to show that a tiny percentage of active managers who did well one year beat the market consistently in the next four years. Here is how he wrote the core evidence:

It included 2,862 broad, actively managed domestic stock mutual funds that were in operation for the 12 months through 2010. The S.&P. Dow Jones team winnowed the funds based on performance. It selected the 25 percent of funds with the best returns over those 12 months — and then asked how many of those funds actually remained in the top quarter in each of the four succeeding 12-month periods through March 2014.

The answer was remarkably low: two.

Outlandishly, this thought is used to promote passive indexes against meritorious and mis-named active managers:

The study seemed to support the considerable body of evidence suggesting that most people shouldn’t even try to beat the market: Just pick low-cost index funds, assemble a balanced and appropriate portfolio for your specific needs, and give up on active fund management.

The data in the study didn’t prove that the mutual fund managers lacked talent or that you couldn’t beat the market. But, as Keith Loggie, the senior director of global research and design at S.&P. Dow Jones Indices, said in an interview last week, the evidence certainly didn’t bolster the case for investing with active fund managers.

The purpose of stock selection and portfolio construction should be to create the most wealth over a ten to twenty-year time frame. Since there are very few talented people who practice long-duration research and stock picking, their absolute skill and relative skill has never been higher. We see nothing happening in the marketplace to show that any significant competition appears to be entering the fray!

We got a kick out of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter and Fiftieth-Anniversary letter. He was frustrated one week after it came out that more people didn’t understand his points better. Below is an excerpt from the Annual Letter:

Over the long term, however, currency-denominated instruments are riskier investments – far riskier investments – than widely-diversified stock portfolios that are bought over time and that are owned in a manner invoking only token fees and commissions. That lesson has not customarily been taught in business schools, where volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk. Though this pedagogic assumption makes for easy teaching, it is dead wrong: Volatility is far from synonymous with risk. Popular formulas that equate the two terms lead students, investors and CEOs astray.

It is true, of course, that owning equities for a day or a week or a year is far riskier (in both nominal and purchasing-power terms) than leaving funds in cash-equivalents.

Buffett directly refutes the usefulness of the issue Loggie raised. The S&P Dow Jones Indices’ data provided to Loggie showed who could consistently beat the market every year and/or 75% of their peers. Buffett would argue this only matters if you measure risk via volatility. What Buffett is trying to say, and what marketplace participants don’t understand, is that a lack of patience is killing active management and it deserves its misplaced name!

Buffett selected the Sequoia Fund in 1970 to send his partnership clients to for diversified common stock ownership. It verifies what Sommer and the research point out. In the first 44 years of existence, it only beat the market in 24 of the 44 calendar years. However, it turned each $10,000 in Sequoia Fund into almost $4 million, while the S&P 500 Index grew it to $965,000! The wealth creation of the Sequoia Fund was over four times the S&P 500 Index with much higher annual expenses included. The Sommer piece included accurate information, but it missed the whole point of investing and the value in selecting a long-duration stock-picking organization.

Let’s sum this up very clearly for our readers: we believe a small percentage of active manager’s limit their activity in a way that allows the wealth creating ability of the underlying companies to shine through their portfolio results. Mr. Mauboussin and other smart mathematicians are trying to see if someone can make constant changes and have a positive impact. In aggregate, it appears that they cannot.

Mr. Buffett argues that the commissions and fees eat up the benefit of most of today’s active management stock selection skills. Mr. Sommer and the passive index/smart beta cheering squads have confused the ultimate goals of long-duration common stock ownership. Supposedly, the passive crowd doesn’t care about the variability of returns or the volatility. They only seem to care when they can use it to criticize the active management community.

Here is a more important question to ask when hiring an active manager: can hiring this organization cause us to create more wealth in U.S. equity ownership than a comparable index can over the next ten years to twenty years? If the answer is yes, you could have something worthy.

The information contained in this newsletter represents SCM’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve month period is available upon request.

This Newsletter and others are available at smeadcap.com